Ancient Israelite Cosmogeography

Introduction

The recently released images of our universe captured by the James Webb space telescope bring home just how ancient and vast it is. Currently, the universe is believed to be 13.8 billion years old, and while we don’t know how large the entire universe is, the observable universe is estimated to be around 93 billion light years in diameter, and consists of around 200 billion galaxies.

The current view of the universe as an unimaginably vast expanse containing hundreds of billions of galaxies is a fairly recent view, dating back around 100 years. Prior to the early 20th century, astronomers believed the Milky Way composed the entire universe, and what we now know as galaxies were called spiral nebulae and believed to be located in the far reaches of the Milky Way. We know that the sun is not the centre of the universe, but that view only appeared in the late 18th to early 19th centuries following considerable astronomical observation and theorising. Heliocentric cosmology, which argues that the earth revolves around the Sun was famously advanced in 1543 by Nicolaus Copernicus, though was first proposed by the Greek philosopher Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BC. Belief in a spherical earth first appeared among a number of Pythagorean philosophers in the 5th century BC. Prior to then, ancient people believed that the earth was flat, covered by a solid dome, and lay at the centre of the universe.

As the Judeans went into exile prior to the first documented evidence of belief in a spherical earth, it is quite likely that the ancient Israelite conception of the universe was radically different to that which we hold today. As the following discussion will show, this is indeed the case, and like their neighbours in the ancient Near East, the ancient Israelites believed the earth to be flat, covered with a solid firmament separating waters above from below in which were set the sun, moon, and stars, and above which was enthroned God.

This makes sense when we consider that our modern view of the universe is just that, one which is the result of considerable scientific labour that simply did not exist in the Biblical world. Therefore, if the Bible referred to the world using scientifically accurate concepts, it would have almost certainly been incomprehensible. After all, the purpose of the Bible was not to instruct humanity on science, but reveal God’s will to humanity, and in order to do that as accurately as possible, it needs to take into account the worldview of the target audience.

The cosmology of the ancient Near East

Old Testament scholar Kyle Greenwood states that common to the civilisations of the ancient Near East was a belief in a three-tiered cosmos of heavens, earth and sea:

Although their views were not necessarily in full agreement on every point, there was a general consensus that the cosmos consisted of three tiers: heavens, earth and sea. According to the evidence, therefore, this viewpoint was held throughout the ancient Near East, from Egypt to Anatolia, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf. It is found in mythological texts, military annals, historiography, prayers and hymns, coffin texts, incantations and spells, and iconography. In short, this three-tiered cosmology permeated the ancient world. [1]

|

| Figure 1 - Three tiered cosmology |

Earth

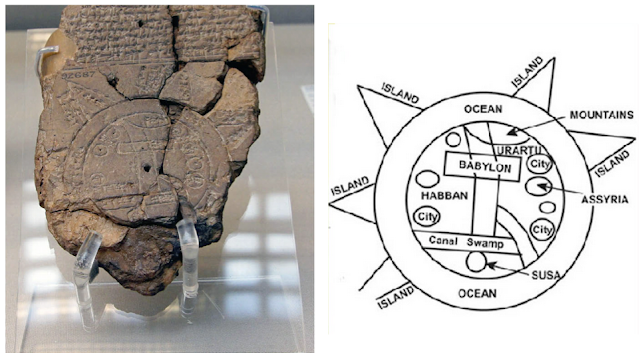

While we now know the earth to be a sphere, the civilisations of the Ancient Near East, like all other cultures believed the earth to be a flat disc, surrounded by water. We can see this in the Babylonian Map of the World, a clay tablet dating to between the 7th-9th centuries BCE, depicting Mesopotamia as being surrounded by a circular ocean. Similarly, a 4th century BCE Egyptian sarcophagus depicts the earth as a flat disc surrounded by a circular ocean.

Figure 2 - Babylonian Map of the World

Figure 3 - Egyptian sarcophagus depiction of world

Ancient Near Eastern cultures

were not in agreement as to how the earth managed to remain afloat given it was

surrounded by water. One idea was that the earth floated, while another was

that giant pillars supported it. A late 2nd millennium Babylonian

boundary marker depicts the earth as seen from this second perspective, with

giant pillars arising from the cosmic sea below the earth supporting the disc

of the earth.

Figure 4 - 2nd millennium BCE Babylonian boundary marker depicting flat earth

The concept of the earth as a disc floating on a cosmic sea is found primarily in Egyptian texts, but we see instances of it in Mesopotamian texts, such as the Founding of Eridu, which is an account of how the Babylonian god Marduk created the earth, followed by the construction of his temple. In this account, we see the earth being set on water:

17 Marduk constructed a raft on the surface of the waters,

18 He made earth and heaped it up on the raft.[2]

Heavens

While views on the exact structure of the sky varied across ancient Near Eastern cultures, there was agreement across these cultures that the sky was solid. Greenwood states that:

It was a nearly universal truth that the sky was a solid structure. In Egypt, it was a flat roof, whereas in Mesopotamia it was dome-shaped. The solidity of the sky was necessary for several reasons. First, as we will see in our discussion on the sea, it served as a barrier for the upper waters. Second, it provided a floor for the heavenly deities and their abodes. Third, it was the ceiling to which the celestial bodies were fixed. In any case, it is best to think of the sky as a firmament, a firm barrier between the sky and heaven.[3]

Based on evidence such as rain or meteorites, ancient civilisations speculated that the sky was made from either water or stone.[4] The first millennium BCE Akkadian text KAR 307 explicitly states that the heavens were made from stone:

30. The Upper Heavens are luludānītu-stone. They belong to Anu. He settled the 300 Igigi inside.

31. The Middle Heavens are saggilmud-stone. They belong to the Igigi. Bel sat on the high dais inside,

32. in the lapis lazuli sanctuary. He made a lamp of electrum shine inside.

33. The Lower Heavens are jasper. They belong to the stars. He drew the constellations of the gods on them.[5]

Greenwood states that Egyptian speculation on the nature of heaven was less specific other than arguing for a watery nature to allow the sun god to sail on its surface, something that the classic image of Nut, goddess of the sky being supported by the god Shu shows.

Figure 5 - Sky goddess Nut being supported by Shu

Being

solid, the sky required support. Egyptians believed the earth was supported

either by pillars or by mountains. The Hebrew scholar J. Edward Wright states,

“The celestial plane itself is either supported by pillars, staves, or

scepters, or is set on top of the mountains at the extreme ends of the earth”.[6]

The Mesopotamians argued either for the Egyptian view of mountains supporting

heaven, or viewed heaven like a tent supported by poles and lines. Wayne

Horowitz refers to the creation epic Enuma Elish that describes how the god

Mardul created the heavens out of the corpse of the slain god Tiamat:

A number of texts refer to cosmic bonds, including ‘bonds’ (riksu, markasu), ‘lead-ropes’ (ṣerretu), and the durmāḫu (‘great bond’), which secure the heavens in place. The most complete explanation of how the heavens are secured is found in Ee V 59–62…Here Marduk twists Tiamat’s tail into the durmāḫu, and uses this durmāḫu to keep the heavens in place over the earth’s surface and Apsu. Then, Marduk uses Tiamat’s crotch as a wedge to hoist the heavens upwards and keep the heavens from falling. Later in Ee V 65–68, Marduk secures the riksu ‘bonds’ of heaven and earth and fastens ṣerretu ‘lead-ropes’, which he hands to Ea in the Apsu. These lead-ropes may be tethered to higher regions of the Universe, and Ea, the lord of the bottom region in Enuma Elish, may hold these lead-ropes to keep the higher regions from floating away[7]

The heavens could be further subdivided into the lower heavens, which contained the sun, moon, and stars, and the upper heavens above the firmament, which were the domain of the gods. The sun disc tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina provides a clear description of this Mesopotamian view of the upper heavens. Wright comments:

The depiction on this tablet…shows Shamash enthroned as king in heaven. Shamash is the large figure on the right seated on a throne that has some zoomorphic characteristics. Above his head are the symbols of the celestial gods Sin (moon), Shamash (sun), and Ishtar (star). The wavy lines at the bottom of this scene indicate water, and beneath the waters is a solid base in which four stars are inscribed. These waters, then, are the celestial waters above the sky. This tablet depicts the god Shamash enthroned as king in the heavenly realm above the stars and the celestial ocean.[8]

Figure 6 - Sun Disc Tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina

Sea

The third tier of the cosmos in ancient Near Eastern cosmogeography is the sea. Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures believed the earth to have been surrounded by water around, above, and below. As Biblical scholar Paul Seely in a comprehensive examination of ancient views on the earth and sea says:

In summary it is clear that ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians believed that the earth, a flat circular disc, was surrounded by a single circular sea. In addition they believed that the earth floated on this sea and that it was this underlying sea which supplied the water in springs, wells and all rivers including the mighty Nile and Euphrates.[9]

Greenwood notes that the ancient world believed the earth arose out of the cosmic ocean, and either floated on it or was supported by pillars. Furthermore, the sky served as a barrier to stop the upper waters from crashing on the earth:

At its inception, a barrier, or firmament, was placed over the earth to protect it from the upper waters. If not for these cosmic barriers, the cosmic ocean’s destructive torrent would bring deluge to the earth by breaking through the firmament, bursting through springs of the deep or crashing over the shores. [10]

As the sky was believed to hold back the upper waters, ancients Mesopotamians believed that these waters above were the source of rain:

The tradition of watery heavens almost certainly derives from the observation that waters fell from the heavens in the form of precipitation. This observation is reflected by close connections between Sumerian and Akkadian names for heaven and words for ‘rain’. […]

The phenomenon of rainfall is explained in different ways. In the Lamaštu incantation 4R2 58 // PBS I/2 113, dew is connected in some way with the stars (see p. 244). In Sumerian texts, rain issues out of cosmic teats called ubur.an.na ‘teat of heaven’, which serve as rain ducts in the sky.[11]

Ancient Egypt depended more on the Nile for water than precipitation, so while believing the sky to be solid and holding back water did not see this as the primary source of water.

Ancient Israelite Cosmology

Having outlined ancient Near Eastern cosmology, we are now in a position to see how the cosmology of ancient Israel compared with that of its neighbours. Given the allusion to ANE mythology, it is important here to stress that cosmology and mythology were not inseparable. The example of Egypt and Mesopotamia make this clear. While they had different mythologies, they all shared the same three-tiered cosmology of solid heaven, flat earth, and surrounding cosmic sea. Therefore, it is not out of the question that ancient Israel, being part of the ancient Near East while having a radically different view of the divine would also share the same three-tiered cosmology. Greenwood argues that this is the case:

Since the ancient concept of the three-tiered cosmos was based on observational analysis rather than theological or philosophical grounds, it should not surprise us that the biblical authors also adhered to this cosmological construct.[12]

Figure 7 - Israelite conception of the world. Illustration from Ben Stanhope (Mis)interpreting Genesis: How the Creation Museum Misunderstands the Ancient Near Eastern Context of the Bible, p 88

Evidence for belief in a three-tiered cosmology in the Bible

can be seen in four places in the Bible:

Ex 20:11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.

Neh 9:6 And Ezra said: “You are the LORD, you alone; you have made heaven, the heaven of heavens, with all their host, the earth and all that is on it, the seas and all that is in them.

Prov 3:19-20 The LORD by wisdom founded the earth; by understanding he established the heavens; by his knowledge the deeps broke open, and the clouds drop down the dew.

Rev 14:7 He said in a loud voice, “Fear God and give him glory, for the hour of his judgment has come; and worship him who made heaven and earth, the sea and the springs of water.”

This is strongly suggestive of ancient Israel also sharing a three-tiered cosmology, but we will need further work to elaborate the details of an ancient Israelite cosmology.

The Firmament and the Waters Above

We don’t need to read far into the Bible before we get an introduction to ancient Israelite cosmogeography. Genesis 1:6-8 outlines the creation of a solid firmament whose function was to separate waters above from waters below:

6 And God said, “Let there be a dome in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” 7 So God made the dome and separated the waters that were under the dome from the waters that were above the dome. And it was so. 8 God called the dome Sky. And there was evening and there was morning, the second day.

and to be the location of the sun, moon, and stars which were embedded in this firmament as v14-15 show:

14 And God said, “Let there be lights in the dome of the sky to separate the day from the night; and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years, 15 and let them be lights in the dome of the sky to give light upon the earth.” And it was so.

Some translations use the word ‘expanse’ instead of ‘firmament’, based on a misguided attempt to read modern science into the creation narrative, but the NRSV better translates the underlying meaning of the Hebrew word raqia‘.

The verbal form of raqia‘ means to spread out, beat out, stamp out or trample and is often used with respect to beating out metal sheets:

Ex 39:3 Gold leaf was hammered out and cut into threads to work into the blue, purple, and crimson yarns and into the fine twisted linen, in skilled design.

Num 16:39 So Eleazar the priest took the bronze censers that had been presented by those who were burned; and they were hammered out as a covering for the altar.

Job 37:18 Can you, like him, spread out the skies, hard as a molten mirror?

The Job reference is of course directly relevant to creation, a point David Clines makes in his commentary on Job:

The picture here is typical of Hebrew cosmology. The sky is viewed as a solid, but thin, sheet of beaten metal (a “firmament,” רקיע), as in Gen 1:7. Above it are storehouses for the rain, snow, and hail (38:22) that descend to the earth through the “windows of heaven” (Gen 7:11). In the firmament are fixed the sun, moon, and stars (Gen 1:14, 15, 17), so we can read of the “shining of the firmament” (Dan 12:3).[13]

Here we see one major point of agreement with ANE cosmogeography in that ancient Israelites also believed in a solid sky holding back waters above which were the source of rain.

Assyriologist Francesca Rochberg, in discussing the history of the waters above the firmament likewise agrees that the firmament of Genesis is something solid. She says:

The author of Genesis calls the firmament rāqî‘a “a plate” or “vault,” from the root rq‘ meaning “to tread or stamp with the feet, to spread out, to beat or hammer out (metals) or apply a plating,” as in “the birds of the skies will fly ‘across the surface of the plate of the skies,’ (Gen. 1:20) or “Yhwh sets the luminaries into the plating of the sky” (Gen. 1:17). [p. 75]. This would seem to be the source for the common expression “vault of heaven.” The rendering of the Hebrew rāqî‘a in the Septuagint became stereoma “a firm or solid structure” from steresein “to make firm or sol[i]d.” In the Vulgate, the equivalent firmamentum suggested something “which strengthens or supports.”[14]

Linguist John Roberts in a comprehensive study of biblical cosmology and its implications for translation declares that

the only denotation of rāqîᵃʿ that is faithful to its lexical meaning and coherent with the Hebrew text in Gen 1.1–2.3 is the one that refers to a literal dome or vault across the sky. Conceptually, such a dome would need to be something solid enough to hold the waters above up.[15]

We saw earlier that in Mesopotamian cosmogeography, the gods were found above the solid sky. We see this in Ex 24:9-10

9 Then Moses and Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel went up, 10 and they saw the God of Israel. Under his feet there was something like a pavement of sapphire stone, like the very heaven for clearness.

Perhaps the most explicit statement placing God above the solid firmament is in Ezekiel 1:22-23,25-26:

22 Over the heads of the living creatures there was something like a dome, shining like crystal, spread out above their heads. 23 Under the dome their wings were stretched out straight, one toward another; and each of the creatures had two wings covering its body…25 And there came a voice from above the dome over their heads; when they stopped, they let down their wings. 26 And above the dome over their heads there was something like a throne, in appearance like sapphire; and seated above the likeness of a throne was something that seemed like a human form.

Figure 8 - Israelite conception of the world. Source: Othmar Keel and Silvia Shroer Creation: Biblical Theologies in the Context of the Ancient Near East, p 83

Biblical scholar Ben Stanhope in his examination of ancient Hebrew cosmology reminds us that:

We know this passage is describing a representation of the sky because, as a noun, the Bible uses this word raqia 17 times across Genesis, the Psalms, Ezekiel and Daniel. In every single other case, it refers to the sky.[16] (Emphasis in original)

A number of modern translations, arguably in an attempt to try to read modern astronomy into the Biblical text render raqia‘ as expanse, but Roberts points out that this translation is inadmissible:

We would argue, however, that translating rāqîᵃʿ with expanse or space or horizon is inaccurate in each case. We have argued, and many biblical exegetes agree, that the lexical meaning of rāqîᵃʿ is that of a flat plane, such as a plate (of metal, glass) or a sheet (of fabric, metal). The verb expand, from which the noun expanse is derived, means to increase in size, more specifically, to increase in amount or volume. For example, a property of a gas is that a gas will expand to fill whatever space it occupies. COBUILD says for its definition of the word expanse that “an expanse of sea, sky, etc. is a very large amount of it that you can see from a particular place.” Therefore the intensional meaning of the English word expanse includes the notion of “large amount of” which the Hebrew word rāqîᵃʿ does not have as part of its intensional meaning. In addition, the Hebrew word rāqîᵃʿ has as part of its intensional meaning something substantive, capable of holding the waters of the heavens in place. The English word expanse lacks this semantic content in its intensional meaning. Therefore expanse is an inaccurate translational equivalent for rāqîᵃʿ.[17]

The modern scholarly consensus that raqia‘ in the OT refers to a slid structure is quite strong, a point OT scholar Peter Enns makes:

The solid nature of the raqia is well established. It is not the result of an anti-Christian conspiracy to find errors in the Bible, but the “solid” result of scholars doing their job. This does not mean that there can be no discussion or debate. But, to introduce a novel interpretation of raqia would require new evidence or at least a reconsideration of the evidence we have that would be compelling to those who do not have a vested religious interest in maintaining one view or another.[18]

The Firmament in Jewish and early Christian Cosmology

Some modern Bible verses translate raqia‘ as expanse, arguably motivated by the need to reconcile modern cosmology with the creation narratives. This is however a mistake as it presupposes that the Bible would reflect modern cosmology, rather than the worldview of the audience to which it was originally given. The reality is that we do not find a modern scientific worldview reflected in the Bible. Rather, as the respected OT scholar John Walton notes:

Genesis 1 is ancient cosmology. That is, it does not attempt to describe cosmology in modern terms or address modern questions. The Israelites received no revelation to update or modify their “scientific” understanding of the cosmos. They did not know that stars were suns; they did not know that the earth was spherical and moving through space; they did not know that the sun was much further away than the moon, or even further than the birds flying in the air. They believed that the sky was material (not vaporous), solid enough to support the residence of deity as well as to hold back waters. In these ways, and many others, they thought about the cosmos in much the same way that anyone in the ancient world thought, and not at all like anyone thinks today. And God did not think it important to revise their thinking.[19]

If the Bible did reflect a modern cosmology then it is reasonable to assume that its earliest interpreters – Jewish and Christian – would have noted that. When we look at Jewish and early Christian readings of the Bible, we see continuity with an ancient Near Eastern cosmology:

Then God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it be separating between the upper waters and the lower waters.” Targ. Pseu. Jon. Gen 1:6

Then God made the firmament (its thickness three finger breadths), between the sides of the heavens and the waters of the ocean. And He separated between the waters that were below the firmament and between the waters that were above, in the canopy of the firmament. And it was so. Targ Pseu. Jon. Gen 1:7

“Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, the middle layer of water solidified, and the nether heavens and the uppermost heavens were formed. Rab said: [God's] handiwork [the heavens] was in fluid form, and on the second day it congealed; thus Let there be a firmament means ‘Let the firmament be made strong*. R. Judah b. R. Simon said: Let a lining be made for the firmament, as you read, And they did beat the gold into thin plates…R. Simon said: The fire came forth from above and burnished the face of the firmament.” Gen. Rab. 4:2

“R. Phinehas said in R. Oshaya’s name: As there is a void between the earth and the firmament, so is there a void between the firmament and the upper waters, as it is written, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, meaning, midway between them. R. Tanhuma said: I will state the proof. If it said, And God made the firmament, and He divided between the waters . . . which are upon the firmament, I would say that the water lies directly upon the firmament itself.” Gen. Rab. 4:3

“…when they had built the tower to the height of four hundred and sixty-three cubits. And they took a gimlet, and sought to pierce the heaven, saying, Let us see (whether) the heaven is made of clay, or of brass, or of iron.” 3 Apoc. Bar. 7

And on the second day he made the firmament in the midst of the water. And the waters were divided on that day. One half of them went up above, and one half of them went down beneath the firmament (which is) in the middle over the surface of all of the earth. And he made only this (one) work on the second day. Jubilees 2:4

It is easy to multiply examples but the example has been made. Judaism from the Second Temple period onwards clearly did not think the Bible taught anything resembling a modern view of the universe. In his study on Rabbinic cosmology, Moshe Simon-Shoshan states:

The rabbis’ view of the nature and structure of the heavens closely parallels Ancient Near Eastern perceptions on the matter, both in its broader conception and in many of its details. Though the rabbi’s main source was certainly the Bible, they very likely had indirect access to other Ancient Near Eastern traditions about the heavens. Several of the rabbis’ ideas about the heavens that have no source in the Bible have precedence in various Mesopotamian sources.[20]

While the Greek belief in a spherical earth can be found in early Christianity, this coexisted with belief in a solid firmament and a cosmic ocean above it:

“But after that he makes the firmament, that is, the corporeal heaven. For every corporeal object is, without doubt, firm and solid; and it is this which “divides the water which is above heaven from the water which is below heaven.” Origen. Homily on Genesis

“If the nature of the elements is taken into consideration, how it is possible for the firmament to be stable between the waters? The one is liquid, the other solid; one is active, the other, passive.” Ambrose. Hexameron. Bk II Ch 2.48

“…’And he called the firmament, heaven.’ In a general way, He would seem to have said above that heaven was made in the beginning so as to take in the entire fabric of celestial creation, and that here the specific solidity of this exterior firmament is meant.” ibid. 2.62

“This firmament cannot be broken, you see, without a noise. It also is called a firmament because it is not weak nor without resistance…the firmament is called because of its firmness or because it has been made firm by divine power..” ibid. 2.62

Even by the Reformation period, Christians were still struggling to reconcile Biblical cosmology with current knowledge. Luther declared:

But what is most remarkable is that Moses clearly makes three divisions. He places the firmament in the middle, between the waters. I might readily imagine that the firmament is the uppermost mass of all and that the waters which are in suspension, not over but under the heaven are the clouds which we observe, so that the waters separated from our waters on the earth. But Moses says in plain words that the waters were above and below the firmament. Here I, therefore, take my reason captive and subscribe to the Word even though I do not understand it.[21]

Conclusion

I have summarised ancient Near Eastern views on the nature of the cosmos and shown that while there were variations between cultures, what united them was a belief in a tripartite cosmos of heavens, earth, and seas, with earth being a solid disc covered by a solid sky above which lay an ocean. We have seen that ancient Israel shared this common view of the cosmos and believed the earth to be flat, covered by a solid dome in which were set the sun, moon, and stars, supporting a celestial ocean, above which was enthroned YHWH. Later Jewish and Christian views on the nature of the cosmos largely reflected this, with belief in a solid firmament and waters above persisting even after the Christian world accepted the Greek view of a spherical earth.

That the Bible reflects a prescientific view of the world should not surprise us if we take a moment to reflect on the fact that our understanding of the universe has changed over time. As I pointed out earlier, even something as simple as recognising the universe consists of billions of galaxies is barely a century old. John Walton ably points out the problems with ensuring the Bible harmonised with science:

If God were intent on making his revelation correspond to science, we have to ask which science…Science moves forward as ideas are tested and new ones replace old ones. So if God aligned revelation with one particular science, it would have been unintelligible to people who lived prior to the time of that science, and it would be obsolete to those who live after that time. [22]

Cosmology is not the only area in which the Bible reflects a prescientific understanding of the natural world. We know that the brain is the seat of our consciousness, but this was not recognised by the ancient world. It is well known for example that the Egyptians thought the brain to be useless and routinely discarded them when embalming the body. The Bible likewise reflects this premodern view of anatomy. There is no unique word for brain in the Old Testament. Instead, the Bible declares that the heart and the kidneys were the seat of the consciousness. Renal physician Joel Kopple writing in the American Journal of Nephrology states

In the Bible, the kidneys were considered to be associated with the innermost part of the personality. They were viewed as central to the soul and to morality, The kidneys were perceived as the source of impetus for moral yearning, a force for moral or righteous action, and as capable of engendering feelings of guilt or moral approval. The kidney was also represented as a vehicle or medium through which God examined the moral nature or worth of man and as a target organ for God’s punishment of humans for immoral behavior.[23]

Examples of where the Bible refers to the kidneys where we would refer to the mind include:

Psa 7:9 O let the evil of the wicked come to an end, but establish the righteous, you who test the minds and hearts, O righteous God.

Psa 26:2 Prove me, O Lord, and try me; test my heart and mind.

Psa 16:7 I bless the Lord who gives me counsel; in the night also my heart instructs me.

Psa 73:21 When my soul was embittered, when I was pricked in heart

If we believe that the Bible must be concordant with modern science in every detail, then we have a major problem as the Bible when read literally declares that our hearts and kidneys rather than our brains are the seat of thought. What we have here instead is an example of accommodation, where God frames his words in culturally relevant terms that would be readily understandable by the original audience. In other words, rather than waste time in trying to teach the original audience modern physiology, God contextualised his message in terms readily understandable to them. Likewise, rather than try to teach the ancient Israelites modern astronomy, God adapted his message to the then-accepted view of cosmology.

In his commentary on Genesis, John Calvin when commenting on the firmament notes the problems with taking the text literally with its reference to waters above the firmament:

Moses describes the special use of this expanse, “to divide the waters from the waters,” from which words arises a great difficulty. For it appears opposed to common sense, and quite incredible, that there should be waters above the heaven. Hence some resort to allegory, and philosophize concerning angels; but quite beside the purpose. For, to my mind, this is a certain principle, that nothing is here treated of but the visible form of the world. He who would learn astronomy, and other recondite arts, let him go elsewhere. Here the Spirit of God would teach all men without exception; and therefore what Gregory declares falsely and in vain respecting statues and pictures is truly applicable to the history of the creation, namely, that it is the book of the unlearned.[24]

Calvin’s remarks that those who would learn astronomy should go elsewhere and that the Bible is the book of the unlearned can be seen as an early example of accommodation, where God does not seek to teach modern scientific ideas but rather tailors the message to the level of the ‘unlearned’.

Old Testament scholar Kenton Sparks notes how this principle of divine accommodation is one that takes into account the fact humans are limited creatures:

Accommodation is God’s adoption in inscripturation of the human audience’s finite and fallen perspective. Its underlying conceptual assumption is that in many cases God does not correct our mistaken human viewpoints but merely assumes them in order to communicate with us.[25]

Were God to have made the references to the cosmos in the Bible fully concordant with reality, it is likely that the message would have been difficult or impossible to fully understand. Paul Seely has noted that when 16th century Jesuit missionaries visited China, they commented that their lack of belief in a solid firmament was “one of the absurdities of the Chinese.”[26] By framing the message to meet the audience rather than insist on being scientifically accurate, one can see that God has chosen to remove barriers to understanding.

For us, the fact that the Bible accommodates prescientific view on cosmology should cause no concern. Instead it is more evidence of God’s grace as it shows he is willing to meet humans where they stand. It also means that there is no need to spend time either denying modern science or trying to harmonise the Bible with contemporary science as these were simply not an issue for God.

Appendix 1

The Hebrew word translated as firmament, raqia' occurs 19 times in the OT. Many of these occur in the Genesis narrative. The remainder occur either in the Psalms or Ezekiel and Daniel:

Gen 1v6 Then God said, “Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.”

Gen 1v7 God made the expanse, and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so.

Gen 1v8 God called the expanse heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.

Gen 1v14 Then God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years;

Gen 1v15 and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth”; and it was so.

Gen 1v17 God placed them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth,

Gen 1v20 Then God said, “Let the waters teem with swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth in the open expanse of the heavens.”

Psa 19v1 The heavens are telling of the glory of God; And their expanse is declaring the work of His hands

Psa 150v1 Praise the Lord! Praise God in His sanctuary; Praise Him in His mighty expanse.

Ezek 1v22 Now over the heads of the living beings there was something like an expanse, like the awesome gleam of crystal, spread out over their heads.

Ezek 1v23 Under the expanse their wings were stretched out straight, one toward the other; each one also had two wings covering its body on the one side and on the other.

Ezek 1v25 And there came a voice from above the expanse that was over their heads; whenever they stood still, they dropped their wings.

Ezek 1v26 Now above the expanse that was over their heads there was something resembling a throne, like lapis lazuli in appearance; and on that which resembled a throne, high up, was a figure with the appearance of a man.

Ezek 10v1 Then I looked, and behold, in the expanse that was over the heads of the cherubim something like a sapphire stone, in appearance resembling a throne, appeared above them.

Dan 12v3 “Those who have insight will shine brightly like the brightness of the expanse of heaven, and those who lead the many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.

Appendix 2 – Conservative misunderstanding of raqia‘

Many theologically conservative exegetes have traditionally argued that raqia' means expanse or space. For example, the New Strong's Dictionary defines it as “an expanse, ie the firmament or (appar) visible arch of the sky :— firmament.”[27] The Bible Knowledge Commentary's observation on Gen 1v6-8 argues strongly in favour of raqia' as an expanse:

On the second day God separated the atmospheric waters from the terrestrial waters by an arching expanse, the sky. This suggests that previously there had been a dense moisture enshrouding the earth. God’s work involves making divisions and distinctions.[28]

Walter Kaiser in “The Old Testament Documents”, argues strongly for reading firmament in the Genesis account as an expanse. He writes:

Few results of scholarly thinking have found more unanimity than on the point of linking the Bible's view of the world with ancient cosmology...They talked, it is claimed, about a flat earth...capped allegedly with a solid firmament...The whole flat earth and solid firmament were supported by pillars which stretched up past the underworld of sheol and the 'deep.'

R. Laird Harris has shown that each step in this allegedly biblical diagram depends more on the ingenuity of the modern scholars than it does on the assertions of the original writers of Scripture. To begin with, nowhere does the Hebrew text state or imply that the raqia (often translated "firmament" but better translated as "expanse") is solid or firm. It is simply an "extended surface" or an "expanse." The idea of "firmness" or "solidity" came more from the Latin Vulgate translation of "firmamentum" and the Greek Septuagint translation of steroma than it did from any Hebrew conceptualizations. The "expanse of the heavens did not imply or call for a sort of astrodomelike structure.[29]

However, apart from representing a minority scholarly view (a point he admits obliquely at the start) Kaiser's argument however is unconvincing, and owes more to do with an apologetic agenda than an attempt at serious scholarly exegesis. This interpretation of firmament as expanse barely fits the Genesis narrative, but it falls apart in Ezekiel, where it is obvious that raqia' refers to something solid, and in context is analogous to the firmament in Genesis 1.[30]

In fact, it has been well established that raqia' means in fact a solid expanse (which would be expected from its use in Ezekiel). For example, Brown-Driver-Briggs define raqia as:

†רָקִיעַ S7549 TWOT2217a GK8385 n.m. Gn 1:6 extended surface, (solid) expanse(as if beaten out;cf. Jb 37:18);—abs. ר׳ Ez 1:22 +, cstr. רְ׳ Gn 1:14 +;—G στερέωμα, B firmamentum, cf. Syriac sub √ supr.;— 1. (flat) expanse (as if of ice, cf. כְּעֵין הַקֶרַח), as base, support (WklAltor. Forsch. iv. 347) Ez 1:22, 23, 25 (gloss? cf. Co Toy), v 26 (supporting י׳’s throne) 10:1. Hence (Co Ez 1:22) 2. the vault of heaven, or ‘firmament,’ regarded by Hebrews as solid, and supporting ‘waters’ above it, Gn 1:6, 7(), 8 (called שָׁמַיִם; all P), ψ 19:2 (|| הַשָּׁמַיִם), זֹהַר הָר׳ Dn 12:3; also הַשָּׁמַיִם ר׳ Gn 1:14, 15, 17, עַל־פְּנֵי ר׳ הַשּׁ׳ v 20 (all P). 012ר֫֒קִיעַ עֻזּוֹ ψ 150:1 (sf. ref. to ).[31]

Harper's Bible Dictionary defines it as a:

“division between cosmic waters on the second day of creation (Gen. 1:6-8), forming the sky. One must here imagine a flat earth and a domed expanse of heavens holding back celestial waters from terrestrial. The Hebrew term raqia‘ suggests a thin sheet of beaten metal (cf. Exod. 39:3; Num. 17:3; Jer. 10:9; also Job 37:18). Similar metaphors for sky are found in Homer and Pindar. Job 26:13 depicts God’s breath as the force that calmed (or ‘spread,’ ‘smoothed’ or ‘carpeted’) the heavens. Luminaries were set in the firmament on the fourth day of creation (Gen. 1:14-19). Rains were believed to fall through sluices or windows in its surface (cf. Gen. 7:11).[32]

The Dictionary of Bibical Languages with Semantic Domains (OT) defines it accordingly:

8385 רָקִיעַ (rā∙qîa’): n.masc.; ≡ Str 7549;TWOT 2217a—LN 1.5-1.16 expanse, firmament, i.e., an area of atmospheric space, either relatively close to the ground or in the upper limit of the sky and heavens (Ge 1:6, 7(3x),8, 14, 15, 17, 20; Ps 19:2[EB 1]; 150:1; Eze 1:22, 23, 25, 26; 10:1; Da 12:3), note: though to the modern mind the expanse of the sky is a void of empty space, it is perceived as a “solid” space (hence firmament) and is so a kind of base to hold up highly heavenly objects such as water or a throne, see also domain LN 7.26–7.53[33]

The standard Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon HALOT notes:

רָקִיעַ: רקע, Bauer-L. Heb. 470n; SamP. arqi; MHeb. DSS (Kuhn Konkordanz 208), Sam., JArm., Syr., Mnd. rqiha sky, firmament (Drower-M. Dictionary 437b): cs. רְקִיעַ: the beaten metal plate, or bow; firmament, the firm vault of heaven: Sept. στερέωμα, Vulg. firmamentum; by רָקִיעַ was understood the gigantic heavenly dome which was the source of the light that brooded over the heavenly ocean and of which the dome arched above the earthly globe (see von Rad TWNT 5:501); for bibliography see further Eichrodt Theol. 2/3:57, 130; Westermann BK 1/1:162f; Zimmerli Ezechiel 55; O. Keel Jahwe-Visionen und Siegelkunst 250-255; Reicke-R. Hw. 719.[34]

Lexically, the case for raqia' meaning something solid and beaten out is robust. The evangelical scholar Paul Seely has made a substantive case for raqia' in Gen 1v6-8 to be interpreted as a solid dome. He writes:

The historical evidence, however, which we will set forth in concrete detail, shows that the raqia' was originally conceived of as being solid and not a merely atmospheric expanse. The grammatical evidence from the OT, which we shall examine later, reflects and confirms this conception of solidity. The basic historical fact that defines the meaning of raqia' in Genesis 1 is simply this: all peoples in the ancient world thought of the sky as solid. This concept did not begin with the Greeks.[35]

Seely surveys the cosmological views of many ancient cultures, and finds a near-unanimity in the belief that the sky was solid. In the absence of any clear statement in the Bible that the ancient Hebrew view of the structure of the universe was substantially different to that of their neighbours, the burden of proof lies on the literalist to prove that raqia' in Genesis means expanse or empty space, as opposed to what was universally accepted among the surrounding nations. He continues:

It is true that Genesis 1 is free of the mythological and polytheistic religious concepts of the ancient Near East. Indeed it may well be anti mythological. But, as Bruce Waltke noted when commenting on the higher theology of Israel as it is found in Genesis 1, the religious knowledge of Israel stands in contrast to Israel's scientific knowledge. In addition, the religious knowledge of Israel, though clearly superior to that of its neighbors, was expressed through the religious cultural forms of the time. Temple, priesthood, and sacrifices, for example, were common to all ancient Near Eastern religions. It should not surprise us then to find the religious knowledge of Israel also being expressed through the merely scientific forms of the time.[36]

Appendix 3 – Alleged examples of modern cosmology in the Bible

One common claim made by fundamentalists is that the Bible contains descriptions of the earth that were ahead of their time. Two of these claims are that the Bible describes Earth as a sphere and is suspended in space:

Isa 40:22 It is he who sits above the circle of the earth, and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers;

Job 26:7 He stretches out Zaphon over the void, and hangs the earth upon nothing.

Here, the claims are that the reference in Isaiah to the circle of the earth refers to it being a sphere, while the reference in Job is a description of the earth hanging seemingly unsupported in space. When examined, these claims break down.

The Hebrew word translated as circle in Isa 40:22 is ḥûg, which occurs elsewhere seven times in the OT.

Josh 6:3 You shall march around the city, all the warriors circling the city once. Thus you shall do for six days

Josh 6:11 So the ark of the Lord went around the city, circling it once; and they came into the camp, and spent the night in the camp.

Josh 15:10 and the boundary circles west of Baalah to Mount Seir, passes along to the northern slope of Mount Jearim

Jdg 16:2 The Gazites were told, “Samson has come here.” So they circled around and lay in wait for him all night at the city gate.

Job 26:10 He has described a circle on the face of the waters, at the boundary between light and darkness.

Psa 73:15 If I had said, “I will talk on in this way,” I would have been untrue to the circle of your children.

Pr 8:27 When he established the heavens, I was there, when he drew a circle on the face of the deep

In each of these passages, the context definitely does not support reading ḥûg as a sphere but rather as a circle. Furthermore, keeping in mind the ancient view of the earth as a circular disc covered by a solid firmament, the Isaiah passage with its reference to God sitting above the circle of the earth fits in neatly with the concept of YHWH enthroned above the firmament covering a circular earth.

Ancient writers also read ḥûg as circle rather than sphere. The classicist Robert Schneider

Looking at these usages together, I am hard put to see how anyone could justify rendering chûgh in Isa. 40:22a as "sphericity." The earliest translations of these Scriptures bear this out. In the Septuagint (LXX), the translators render the nominal and verbal forms of chûgh in every case with the Greek gýros (noun), "circle" or "ring," which they use in Isa. 40:22a, or gyróo (verb), "to make or inscribe a circle." Gýros does not mean "sphere," and in fact nowhere in any Greek recension of the Hebrew Scriptures will one find the proper word sphaíra used in this context at all. The history of the formation of the LXX is largely lost, and we do not know if the Prophets were translated in Alexandria as the Torah was in the third century BC. But if they were and if the translators were familiar with the concept of a spherical earth taught at the Museon of Alexandria, then the center of Greek science, they give no hint of it in their translation of chûgh.[37]

Both from context and early reception, it is clear that Isa 40:22 is referring not to a spherical earth, but rather the circle of a flat earth.

Moving to Job 26:7, while a surface literal reading of the verse in isolation may appear to support the claim that it is revealing modern knowledge, reading the passage in context argues against this:

7 He stretches out Zaphon over the void, and hangs the earth upon nothing.

8 He binds up the waters in his thick clouds, and the cloud is not torn open by them.

9 He covers the face of the full moon, and spreads over it his cloud.

10 He has described a circle on the face of the waters, at the boundary between light and darkness.

11 The pillars of heaven tremble, and are astounded at his rebuke.

Verse 10 with its reference to a circle on the face of the waters brings to mind ANE cosmology with a circular sea meeting the sky, while verse 11 clearly refers to the heavens being supported by solid pillars. To read verse 7 as a reference to a spherical earth suspended in space while reading verse 11 as poetry is simply ad hoc reasoning. Given the references in verses 7 and 11 to an ANE cosmology, it is reasonable to argue that verse 7 should likewise be interpreted not as an example of modern science in the Bible, but within an ANE context, which has a flat earth either supported by pillars or floating on the cosmic sea.

Kyle Greenwood raises the possibility of the latter, writing:

Although Hartley does not follow Tur-Sinai’s reading of ṣāpôn, he does surmise that the earth “is being pictured as a disk or a plate floating on the deep.”[38]

Further support for the idea that Job is referring to the earth being suspended over water comes from Othniel Keel who writes:

The earth, on the one hand, receives the light of the heavens, and is consequently a region of life; it ends, on the other hand, in dark, bottomless Chaos. One of Yahweh's great deeds was his establishment of the earth over the abyss of the floods of Chaos. On occasion it is even said that he established it over the void (Job 26:7). He has set a bound which the waters of Chaos (the void) may not pass (Ps 104:9).[39]

Another clue to properly interpreting this passage comes from recognising the parallelism of Hebrew poetry, where the same thought can be expressed in two successive units. The two successive units in Job 26:7 are

Unit 1 – He stretches out Zaphon over the void,

Unit 2 – and hangs the earth upon nothing.

The word for void in the first half of verse 7 is tohu, the same word used to describe the waters of chaos in Gen 1:2. This raises the possibility of the ‘nothing’ being equivalent to the watery chaos, a view which would support a reading of Job 26v7 as referring to the flat disc of the earth being suspended over the watery chaos of the primordial sea. Ben Stanhope concurs, arguing:

In accordance with a main theme of the passage’s chapter, and especially verse 10, most scholars view this nothingness as alluding to the abyss of chaotic waters over which is suspended the terrestrial creation in Job’s cosmology.[40]

Therefore, far from being references to modern science ahead of time, these two passages fit more comfortably in the existing ANE cosmogeography of a flat earth covered by a solid dome over the watery chaos of a cosmic sea.

References

[1] Kyle Greenwood Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 71-72

[2] Lambert, W. G Babylonian Creation Myths (Winona Lake, In: Eisenbrauns, 2013) 373

[3] Greenwood, op cit p 55

[4] Wayne Horowitz, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography, ed. Jerrold S. Cooper, vol. 8, Mesopotamian Civilizations (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2011), 262.

[5] Ibid, p 4.

[6] J Edward Wright The Early History of Heaven (New York, NY: Oxford University Press 2000). 13

[7] Horowitz op cit p265.

[8] Wright, op cit p 36-37

[9] Paul H. Seely, “The Geographical Meaning of ‘Earth’ and ‘Seas’ in Genesis 1:10,” Westminster Theological Journal 59, no. 2 (1997): 246.

[10] Greenwood, op cit p 62-63

[11] Horowitz op cit p 262.

[12] Greenwood, op cit p 72

[13] David J. A. Clines, Job 21–37, vol. 18a, Word Biblical Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2006), 882.

[14] Rochberg, Francesca In the Path of the Moon: Babylonian Celestial Divination and its Legacy. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill 2010, 347

[15] John R. Roberts, “Biblical Cosmology: The Implications for Bible Translation,” Journal of Translation 9.2 (2013), 40.

[16] Stanhope, Ben. (Mis)interpreting Genesis: How the Creation Museum Misunderstands the Ancient Near Eastern Context of the Bible. (Louisville, KY: Scarab Press, 2020.), 98

[17] Roberts, op cit p 41

[18] Pete Enns “The Firmament of Genesis 1 is Solid but That’s Not the Point” BioLogos January 14, 2010

[19] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 14.

[20] Moshe Simon-Shoshan “The Heavens Proclaim the Glory of God” A Study in Rabbinic Cosmology Bekhol DeraKhekha Daehu 20 (2008), 88

[21] Jaroslav Pelikan (ed.), Luther’s Works, Volume 1: Lectures on Genesis, Chapters 1-5, trans. George V. Schick (St. Louis: Concordia, 1958), 26

[22] Walton, op cit, 15.

[23] Kopple, Joel D. “The Biblical View of the Kidney: Am J Nephrol 1994;14:279-280

[24] John Calvin and John King, Commentary on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis, vol. 1 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 79–80.

[25] Kenton Sparks, God’s Words in Human Words (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), p. 243

[26] Paul H. Seely, “The Firmament and the Water above: Part I: The Meaning of Raqiaʿ in Gen 1:6–8,” Westminster Theological Journal 53, no. 2 (1991): 232.

[27] Strong, J. “The New Strong's dictionary of Hebrew and Greek words” (1997, Nashville: Thomas Nelson)

[28] Walvoord, J. F., Zuck, R. B. The Bible Knowledge Commentary : An exposition of the scriptures (1:29). (1985 Wheaton, IL: Victor Books)

[29] Kaiser WC Jr “The Old Testament Documents – Are They Reliable” (IVP 2001) p 75-76. Kaiser does his cause no good however with the decidedly polemic nature of his writing. For example, in footnote 13 on page 75, he describes Bailey's Genesis, Creation as “among the most recent restatements of this scholarly shibboleth."

[30] There is evidence of a more nuanced concept of the firmament in Jewish writings. In “Traditions of the Bible: a guide to the bible as it was at the start of the common era”, (Harvard 1998) James Kugel comments on 4 Ezra 6:41 which described the creation of the 'spirit of the firmament' and the command issued to him to separate the waters. He writes, “Perhaps this angel owes his existence to the understanding, mentioned earlier, of 'firmament; as the name of one part of the heavens, a part in which, arguably, angels dwelt.” p 74. Elsewhere though, there is unambiguous evidence that a belief in the solidity of the firmament existed in ancient Jewish thought. For example, 3 Baruk 3v6-8 states “And the Lord appeared to them and confused their speech, when they had built the tower to the height of four hundred and sixty-three cubits. And they took a gimlet, and sought to pierce the heaven, saying, Let us see (whether) the heaven is made of clay, or of brass, or of iron. When God saw this He did not permit them, but smote them with blindness and confusion of speech, and rendered them as thou seest.”

[31] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. 2000. Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (electronic ed.) (956). Logos Research Systems: Oak Harbor, WA

[32] Achtemeier, P. J., Harper & Row, P., & Society of Biblical Literature. (1985). Harper's Bible Dictionary (1st ed.) (309). San Francisco: Harper & Row.

[33] Swanson, J. (1997) Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains : Hebrew (Old Testament) (electronic ed.) (DBLH 8385). Oak Harbor: Logos Research Systems, Inc.

[34] Koehler, L., Baumgartner, W., Richardson, M., & Stamm, J. J. 1999. The Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament (electronic ed.) (1290). E.J. Brill: Leiden; New York

[35] Seely (1991) op cit p 227-228

[36] ibid p 235

[37] Robert J Schneider “Does the Bible Teach a Spherical Earth” Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 53 (2001):159-169

[38] Greenwood op cit p 79-80

[39] Keel, Othmar. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 55

[40] Stanhope, op cit p 93