One of the most powerful arguments against a global flood is the biogeographical distribution of species. One would expect to see evidence of a radiation of animal life away from Mt Ararat, with animals distributed according to ecological zoning. We don't. The rainforests of Africa, Asia, and South America have radically different fauna. Ditto for the deserts of Africa and Australia. We know that introduced species such as camels flourish in Australia, making their absence here inexplicable if all life radiated out from Mt Ararat.

Robert Roberts made this point in The Visible Hand of God in arguing for a local flood:

There are facts that compel such a conclusion; and as all facts are of God, they must be in agreement. The animals of New Zealand are different from those of Australia. The animals of Australia, again, are different from those of Asia and Europe. These again differ entirely from those of the American continent: all differ from one another: and the fossil remains on all the continents show that this difference has always prevailed. Now if the flood were universal in the absolute sense, it is manifest that these facts could not be explained, for if the animals all over the earth were drowned, and the devastated countries were afterwards replenished from a Noachic centre, the animals of all countries would now show some similarity, instead of consisting of totally different species.

Roberts never accepted common descent and large-scale evolutionary change, but his argument from biogeography not only rules out a global flood, but provides, along with comparative genomics, perhaps the most powerful argument against special creation and in favour of common descent. [1]

When examining the distribution of life across this planet, a number of quirks stand out. Perhaps the most obvious one is that while similar environments can be found across the planet (deserts for example), species are not uniformly distributed across the possible zones in which they could exist. Camels thrive in Australia, but are not indigenous to them. Eucalyptus trees grow quite well outside of Australia, to the point that they are regarded by some as a noxious invasive weed. In general, there is no reason why these organisms are restricted to a subset of the possible ecological zones around the world. Darwin observed in the Origin of Species that:

"In the southern hemisphere, if we compare large tracts of land in Australia, South Africa, and western South America, between latitudes 25 and 35 degrees, we shall find parts extremely similar in all their conditions, yet it would not be possible to point out three faunas and floras more utterly dissimilar. Or, again, we may compare the productions of South America south of latitude 35 degrees with those north of 25 degrees, which consequently are separated by a space of ten degrees of latitude, and are exposed to considerably different conditions; yet they are incomparably more closely related to each other than they are to the productions of Australia or Africa under nearly the same climate. Analogous facts could be given with respect to the inhabitants of the sea." [2]

Another fact is that island life usually closely resembles that on the nearby mainland. Conversely, for oceanic islands far from the mainland, the indigenous life is usually restricted to what can swim, fly or float over. Large mammals, freshwater fish and amphibians are usually not indigenous to oceanic islands, but thrive when introduced.

To this one can add the fact that barriers to migration such as mountains, rivers or large tracts of inhospitable land such as deserts also are correlated to biogeographic variation. Again, Darwin noted:

"A second great fact which strikes us in our general review is, that barriers of any kind, or obstacles to free migration, are related in a close and important manner to the differences between the productions of various regions. We see this in the great difference in nearly all the terrestrial productions of the New and Old Worlds, excepting in the northern parts, where the land almost joins, and where, under a slightly different climate, there might have been free migration for the northern temperate forms, as there now is for the strictly arctic productions. We see the same fact in the great difference between the inhabitants of Australia, Africa, and South America under the same latitude; for these countries are almost as much isolated from each other as is possible. On each continent, also, we see the same fact; for on the opposite sides of lofty and continuous mountain-ranges, and of great deserts and even of large rivers, we find different productions; though as mountain chains, deserts, etc., are not as impassable, or likely to have endured so long, as the oceans separating continents, the differences are very inferior in degree to those characteristic of distinct continents."

As I mentioned earlier, Roberts did not accept evolution. Roberts however showed remarkable insight into biogeography, and his argument that a global flood would show a biogeographic distribution of species which is not seen on this planet is compelling. The same observation also holds with respect to the question of whether life was specially created, or arose via descent with modification, with barriers to the free movement of life such as oceans, deserts, mountains and rivers contributing to the biogeographic distribution of life.

Alfred Wallace, the 19th century naturalist who independently advanced a theory of evolution at the same time as Darwin spent some time in the Indonesian archipelago, and like Darwin noted marked differences in the local flora and fauna. Most noticeably, he discovered that despite being separated by a mere 25 km, the wildlife of the islands of Bali and Lombok were radically different. The wildlife in Bali included monkeys, tapirs and woodpeckers, all of which are native to Asia. Lombok on the other hand had tree kangaroos, cockatoos and brush turkeys which are native to Australia:

"The Australian and Indian regions of Zoology are very strongly contrasted. In one the Marsupial order constitutes the great mass of the mammalia, - in the other not a solitary marsupial animal exists. Marsupials of at least two genera (Cuscus and Belideus) are found all over the Moluccas and in Celebes; but none have been detected in the adjacent islands of Java and Borneo. Of all the varied forms of Quadrumana, Carnivora, Insectivora, and Ruminantia which abound in the western half of the Archipelago, the only genera found in the Moluccas are Paradoxurus and Cervus. The Sciuridæ, so numerous in the western islands, are represented in Celebes by only two or three species, while not one is found further east.

"Birds furnish equally remarkable illustrations. The Australian region is the richest in the world in Parrots; the Asiatic is (of tropical regions) the poorest. Three entire families of the Psittacine order are peculiar to the former region, and two of them, the Cockatoos and the Lories, extend up to its extreme limits, without a solitary species passing into the Indian islands of the Archipelago. The genus Palæornis is, on the other hand, confined with equal strictness to the Indian region. In the Rasorial order, the Phasianidæ are Indian, the Megapodiidæ Australian; but in this case one species of each family just passes the limits into the adjacent region.

"All these groups are common birds in the great Indian islands; they abound everywhere; they are the characteristic features of the ornithology; and it is most striking to a naturalist, on passing the narrow straits of Macassar and Lombock, suddenly to miss them entirely, together with the Quadrumana and Felidæ, the Insectivora and Rodentia, whose varied species people the forests of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo." [3]

Wallace observed that the biogeographic distribution of life is not continuous over the archipelago. In fact, one can demarcate this distribution of life with some accuracy.

The Wallace line passes between Bali and Borneo on one side, and Sulawesi and Lombok on the other, separating the biozones of Asia on the left, and Wallacea on the right. Lyddeker's line conversely separates the biozones of Wallacea and Australia / Papua New Guinea.

Wallacea is the term used to describe the oceanic islands in the Indonesian archipelago that are separated from the Asian and Australian continental shelves by deep water. Unlike the biozones of Asia and Australia which are richly populated with freshwater fish, large mammals or flightless birds related to those from the adjacent continents, Wallacea is poorly represented by these animals. This is what one would expect as the deep water straits form a natural barrier which is difficult to pass. Conversely, birds, reptiles and insects from both biozones are readily able to cross these barriers, and as one would expect, Wallacea has representatives from both biozones.

As Roberts noted, the biogeographic distribution of life is not consistent with a global flood. The biogeographic distribution of species is also not consistent with special creation. There is no reason why Bali and Lombok, which are adjacent small islands with similar climate should have radically different animal life. The same argument applies when we compare the Asian, Wallacean and Australian ecozones - special creation has to convincingly explain why God would restrict the Asian biozone to Asian species, the Australian biozone to Australian species and keep the Wallacean biozone largely free of freshwater fish and mammals. Common descent has little problem explaining this. The deep water straits acted as geographic barriers, preventing Asian and Australian fauna from crossing to the other biozones, and keeping Wallacea largely unpopulated by freshwater fish and large mammals. Smaller animals (birds, insects) conversely are able to fly across these barriers. The pattern of descent with modification seen inside these biozones is generally as one would expect it to be with these barriers to gene flow.

When combined with the theory of plate tectonics, biogeography can readily explain the current distribution of related animals in unconnected parts of the world. Marsupials are presently restricted to Australia, PNG, the southern part of North America and South America. If the continents were fixed, then it would be difficult to explain the current distribution of marsupials without postulating separate origins of marsupials in Australia and the Americas.

The geographic distribution of marsupial fossils through time and a knowledge of plate tectonics resolves this problem. The earliest marsupial, Sinodelphys szalayi is 125 million years old and was found in the Yixian Formation in China [4]. Conversely, Djarthia murgonensis, found in Queensland, Australia is the oldest known Australian marsupial fossil, dating back 54 million years. [5] Fossil marsupials in North America easily predate those in Australia - Kokopellia juddi, a marsupial-like animal discovered in North America has been dated to the early Cretaceous, around 101 million years ago. [6] Marsupial fossils dating to around 64 million years ago have been found in Bolivia [7].

Marsupials first appeared in China, then migrated to North America and moved down to South America. They crossed the Antarctic, and then across to Australia. What would apear to be a puzzle is readily resolved when we look at the biogeographical distribution of marsupials through time.

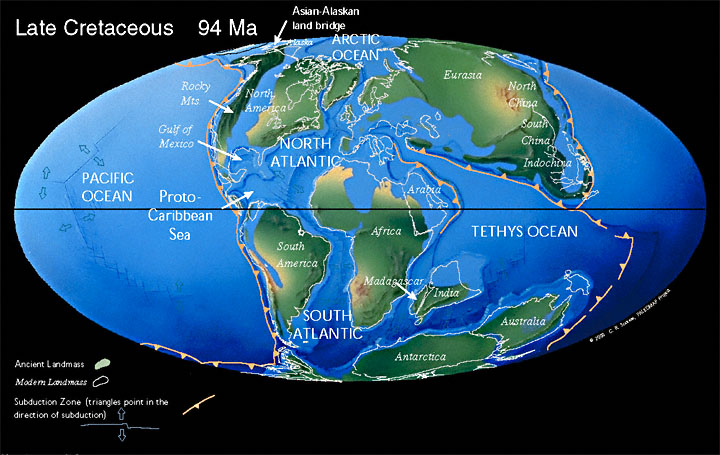

By combining our knowledge of continental drift with the fossil evidence, we can readily account for the biogeographic distribution of marsupials. The National Center for Science Education notes that around 94 million years ago:

"...the southern continents were all connected, North America and Europe were still very close, and South America had not drifted far from North America, allowing dispersal during periods when ocean levels dropped. Marsupials related to North American species colonized Europe briefly, through a northern land bridge, and others colonized South America. Africa was in the process of separating from the supercontinent which also included Antarctica, Australia and South America, so the presence of marsupial fossils in Africa gives a good measure of how quickly they entered South America and dispersed across the supercontinent Gondwana. Fossilized marsupials in Antarctica also allow us to track their dispersal to Australia. This pattern is consistent with the fossil record of placental mammals, and with other lines of evidence...

"As the southern continents drifted apart as well, the marsupial faunas in each isolated continent followed a different path. As Antarctica drifted south towards its current polar position, it became colder and colder, ultimately driving its resident marsupials and palm trees extinct. South American and Australian marsupials produced diverse radiations which filled many of the same ecological niches occupied by placental mammals elsewhere. In the northern continents, which were periodically linked by land bridges, biotic interchanges resulted in periods of intense competition, which seem to have driven the native marsupials extinct.

"When South America drifted north again and connected with North America around 3 million years ago, the Great American Biotic Interchange had the same devastating effect that biotic interchanges had on other marsupial faunas.

The same pattern of diversification and migration seen in marsupials can also be seen in other groups of plants and animals. That consistency between biogeographic and evolutionary patterns provides important evidence about the continuity of the processes driving the evolution and diversification of all life. This continuity is what would be expected of a pattern of common descent. The creationist orchard scheme gives us no reason to predict this pattern.

The reconstruction of the positions of the continents at this time (see below) helps make this clear.

Conclusion

This - needless to say - is merely an introduction to biogeography, but the geographic pattern of life seen now and in the fossil record provides strong evidence against special creation, and for an evolutionary origin of the species. Well before the superabundance of transitional forms in the fossil record were discovered, well before the evidence from molecular genetics sealed the case for common descent, mainstream science had accepted common descent largely on the strength of biogeography, atavisms and comparative anatomy.

References

1. Much of this material previously appeared at my Google+ site

2. Darwin C On the Origin of Species Chapter 12 http://www.classicreader.com/book/107/82/

4. Luo, Zhe-Xi; Ji, Qiang; Wible, John R.; Yuan, Chong-Xi. "An early Cretaceous tribosphenic mammal and metatherian evolution". Science (2003) 302: 1934–1940

5. Beck RMD, Godthelp H, Weisbecker V, Archer M, Hand SJ Australia's Oldest Marsupial Fossils and their Biogeographical Implications. PLoS ONE (2008) 3(3): e1858. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001858

6. Cifelli RL "Early Cretaceous mammal from North America and the evolution of marsupial dental characters" Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (1993) 90:9413-9416

7. Muizon, C., Cifelli, R.L., Paz, R.C., The origin of the dog-like borhyaenoid marsupials of South America. Nature (1997) 389:486–489.